Stoner by John William - Thoughts

- Advik Lahiri

- Mar 10, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 11, 2023

Stoner has been described by some to be the perfect novel. It probably is. Some have called it their favourite novel. Is it mine? I’m not sure about that. Reading Stoner is like living a life. A life that is full of melancholy and quiet love, quiet passions. Stoner is a life defined by stoicism. And thus, it is hard to have a favourite life; but then again, great literature is about giving the reader another life, so maybe that is why many baulk when asked, ‘What is your favourite book?’

This essay seeks to analyse, or at least ruminate over the elements of this book. The main element would be how the aspects of this book culminate to leave such a profound effect on the reader, considering how Stoner only has an ephemeral love of the flesh, an eternal love of the text, and a milquetoast protagonist. Well, that would be the reason why. The melancholy of the text washes over the reader, casting empathy, even sympathy perhaps. Empathy always creates some form of intimate connection between the reader and the text and such is the case with Stoner, except more intense, because the grief is so subtle yet it looms so large, the love is gentle on the outside, but passionate on the inside. It is a text of dualities, that compliment each other in some ways.

Another reason it is so powerful is that the text describes a life in full. There is nothing experimental about the novel in terms of perspective and narration. It is in the third person, and we are raised with Stoner and we die with Stoner. We see an entire life in the text and that too creates a personal bond. The reader is like a spectator, a guardian watching over a professor, hoping he does not encounter harm in his humble life, yet the spectral reader sees the random chances of luck and fortune work against our dear Stoner, and that fills the heart with something dense and sorrowful. Williams uses his prose in interesting ways too. Following some sort of event, Williams will talk about its consequence (something along the lines of, ‘a few years later, Stoner would realise the effect this would have’) and thus he adds a preternaturalness to our role as readers because we know things that Stoner does not, but it also adds solemness because it means this life that we have been following will eventually end and in the vision and mind of the writer, John Williams, Stoner has passed away. This use of prose also reflects on our own lives, showing a finality to decisions, how damning the consequences of a choice can be, and how things are in many ways out of our control.

The very beginning of the book, already sets the tone for the book:

‘William Stoner entered the University of Missouri as a freshman in the year 1910, at the age of nineteen. Eight years later, during the height of World War I, he received his Doctor of Philosophy degree and accepted an instructorship at the same University, where he taught until his death in 1956. He did not rise above the rank of assistant professor, and few students remembered him with any sharpness after they had taken his courses. When he died his colleagues made a memorial contribution of a medieval manuscript to the University library. This manuscript may still be found in the Rare Books Collection, bearing the in-scription: "Presented to the Library of the University of Mis-souri, in memory of William Stoner, Department of English. By his colleagues."

An occasional student who comes upon the name may wonder idly who William Stoner was, but he seldom pursues his curiosity beyond a casual question. Stoner's colleagues, who held him in no particular esteem when he was alive, speak of him rarely now; to the older ones, his name is a reminder of the end that awaits them all, and to the younger ones it is merely a sound which evokes no sense of the past and no identity with which they can associate themselves or their careers.’

These two paragraphs reinforce the motifs of life and death, but they also make it seem like the reader is peeking into a very special, undocumented, and thus even more special part of history. This already creates a strong impression on the reader at the outset of the book, and lays a wreath of gold over the rest of the text. The text and the prose often feel like they are glowing. It is hard to explain why. It likely arises from the intimacy of the text, and the love that we feel for literature, his child, and his colleague turned inamorata. But this aspect of history, also adds to this glowing sensation.

This essay has been quite short and are only a few thoughts about a very good book. One could analyse it much more; it has that potential, and it has that depth. Would I recommend it? If one appreciates the beauty of prose, characters, and life, then yes. This is book is not thrilling (the most thrilling part, are his sexual escapades - yes, that is probably quite thrilling but, spoiler alert, it does not last long; another somewhat thrilling part is probably when Stoner castigates a tricky student, that sets the tone a bit better). This book is deep and subtle and worth appreciating. It is one of the greatest campus novels, and one of the best character studies rendered in often stunning prose. From the both tender and stern Stoner to the cruel silence of his wife, from the joy of his love, to the despair some colleagues cause him, we see it all. To conclude, I think this quote of Viola-Cesario from Twelfth Night by Shakespeare, perfectly describes Stoner as the book and Stoner as the eponymous character.

‘A blank, my lord. She never told her love,

But let concealment like a worm ‘th’bud

Feed on her damask cheek. She pined in thought,

And with a green and yellow melancholy

She sat like Patience on a monument,

Smiling at Grief.’

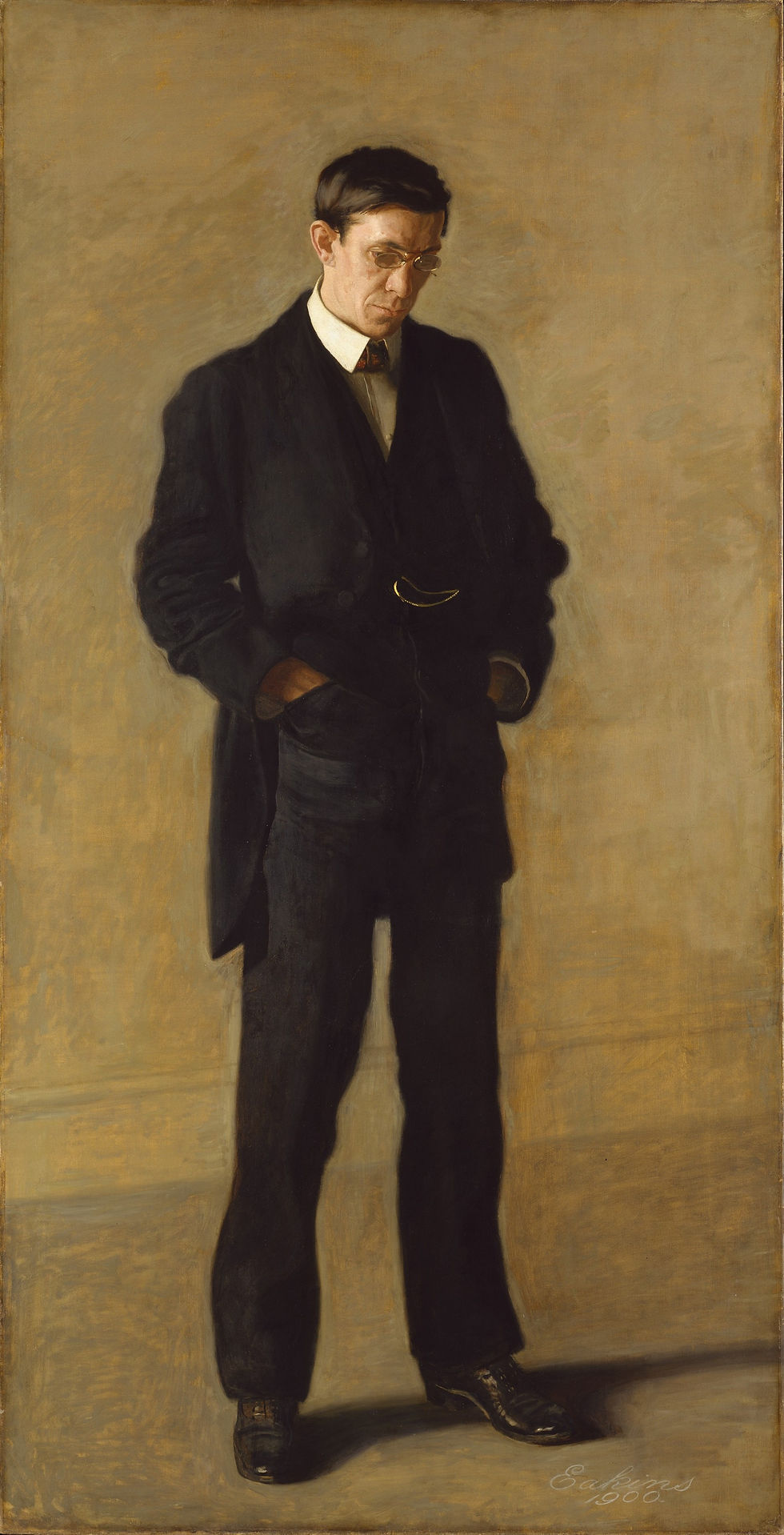

Image Credit: The Thinker: Portrait of Louis N. Kenton by Thomas Eakins https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/10827#fullscreen